My father forced me to go to the polling booth with him every year. Dressed in my Catholic school uniform, I would walk with him to the local polling station, where he would force me to stay in my spot as he moved towards a heavy apparatus that looked like an essential part of Frankenstein’s laboratory. My eyes travel along the route of the snaking black cords that looped on the floor and into the voting machines, where my father seemed to pull little black levers.

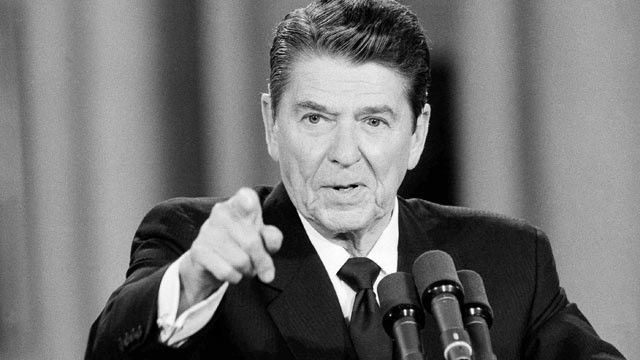

When it was all over, my father would mutter something about Governor Ronald Reagan. He hated Ronald Reagan, whose first name I once believed was “Goddamn”. My father would do anything to eliminate the earth of Reagan, Nixonand even San Francisco’s Mayor Joseph Alioto.

Voting, he used to tell me, was his way of trying to stop the advancement of tyranny.

This was an act of patriotism that my father passed on to both my sister and I. When I was old enough to vote, my father insisted on coming with me to the local voting precinct. I prepared my list of candidates and propositions after perusing the local newspapers and the thick San Francisco voter pamphlet that seemed to be part joke book filled with the colorful names of cab drivers, club owners, strippers and artists who were in search of a seat in local office. I finally settled upon my chosen lists of candidates to reflect my life as a young University college student caught in the romantic throes of toothless punk anarchy. I wanted Jello Biafra of the “Dead Kennedys” to become mayor over Dianne Feinstein, and I wanted California to leave gay people alone.

It was simple. I had spent my high school years participating in marches protesting the reduction in education spending, attempts to build a nuclear power plant on a fault line and Robert Dornan’s repeated attempts to terrorize the gay community. Voting would now allow me an official voice to shout into a vast canyon of ideas that would be molded into laws and leaders.

My father, however, was bitterly disappointed that I had cast my Mayor vote for Jello Biafra, the lead singer of the Dead Kennedys.

“You are stupid,” he said. “What if he wins?”

I tried arguing my point, letting rebellion and angst lace my vitriol. My father closed his eyes when my hair had gone purple and the clothing began to become weird and wicked. On this point, however, he was immovable. He had taught me the importance of voting, and now believed that his general failure to communicate had produced the country’s latest imbecile in fishnet stockings.

Like him, I wanted a better world. My idealism and politics was expressed whenever I sat in cafes with friends, helped put on benefit concerts at the local clubs, wrote about music and film and in college, where my friends and I filled the late night San Francisco airwaves with punk music.

As I grew older, my father frowned when I began to skip the smaller elections. I could hardly juggle work, school and an active social life, and the polling booth only became important for the big issues and candidates.

He began to go alone to the polling station for many years until it was the very last one of his life.

Now blind and in the final stages of mesothelioma, which made breathing impossible, I spent election night with my father. He was far too weak to make it to the polling booth but was desperate to erase all legacies of Ronald Reagan’s presidency from office. With the help of a volunteer from the Democratic party, we spent the next hour helping my father walk the half block distance to a Karate studio so he could cast his final vote.

We would return my father to his favorite chair so he could listen to the television. Participating in his favorite patriotic duty had exhausted him, but he was proud and happy for the few seconds it took for the television to warm up and announce that the Republican candidate had won the presidency. I watched as my father slumped, shook his head and become swallowed in bitterness.

On elections nights, I still picture my father struggling to hold onto my arm as he made his way up the small hill, shuffling his puffy feet that had pulsed like half-filled water balloons in his slippers.

I got the message.

(c) 2014 Slow Suburban Death. All rights reserved.

Be First to Comment