The recent weekend George Washington High School reunion picnic brought out memories of my own time wandering those dark and cold class hallways, where I snuck away from my last class to sit on the football bleachers. There, I could look at the school’s unparalleled view of the Golden Gate Bridge, where painted red towers rose was sometimes capable of rising above the rolling fog, a stark reminder of San Francisco’s beauty. No teachers ever came about to ask the few students on the bleachers to return to class. We were allowed to cut class in peace, although such things are never conducive to academics.

The recent weekend George Washington High School reunion picnic brought out memories of my own time wandering those dark and cold class hallways, where I snuck away from my last class to sit on the football bleachers. There, I could look at the school’s unparalleled view of the Golden Gate Bridge, where painted red towers rose was sometimes capable of rising above the rolling fog, a stark reminder of San Francisco’s beauty. No teachers ever came about to ask the few students on the bleachers to return to class. We were allowed to cut class in peace, although such things are never conducive to academics.

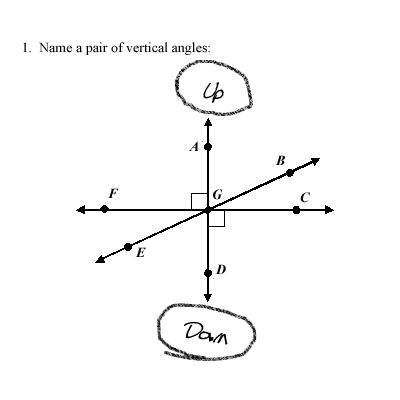

I did not care. I was already a senior, having received my admission letter to the local University of San Francisco, a college, my sister reminded me, that would accept any Catholic, no matter how bad the grades. My grades were always excellent if you removed any memory of my having attended math classes, in which I managed to have a consistent flunk/re-do pass scores. It had been a constant battle since grammar school to keep from drowning in new math, living alongside boxed numbers, percentages, triangles and wondering how long it would take for Daryl to get from point A to F while carrying five pineapples. I seemed to be the eternal flunkie in a classroom filled with overachievers who mastered numbers, born to add and subtract while watching television, playing piano and being spectacular, well-behaved children at the same time.

I was not one of those students. In senior year, I just gave up on the whole thing. I could not face Geometry 2.

I have long struggled with math, although modern science has now diagnosed my issues with floating, disappearing numbers and letters as dyslexia. In the interim, I seemed to waste valuable hours put in by well-meaning tutors. I can still picture the exasperated expression of my childhood tutor, whose mouth would form an O when I I failed to grasp long division. I am pretty sure that she told my mother that I was hopeless, since the only things I could ever recollect of my lessons was that the tutor’s home smelled like chicken adobo. She also had a nasty Siamese cat. To further correct my math issues, my mother made me stare at numbers during one summer. That was the summer I became addicted to Ultraman reruns.

While perseverance was important in grammar school, giving up seemed less time consuming by the time I was pushed into higher version of math in high school. It began during geometry test. My response to the question, “name three different kinds of triangles” was to simply reply 1) Charlies Angles; 2) Los Angles; and 3) Angle Saxon. After flunking that class, I had to do a re-take. I passed that re-take class, but only after swiping a former student’s old model triangle that had been pinned next to the chalkboard and handing it in as my own work. The instructor at the time, a nice gentleman who seemed overwhelmed by the 50+ kids in his classroom at the time, never noticed.

By my senior year, I somehow found myself in the Geometry 2 class. This time, I really tried to apply myself to my work. The teacher was a nice guy who wore soccer jerseys to class and liked to play the radio. He actually had “Baba O’Reilly” on the radio once, but some kid screamed bloody murder and the station was changed to a pop station. Therein was my first reason to dislike the class. The upside, however, was that I got to sit next to my neighbor down the block, a guy who played drums well and owned a pet tarantula. He never understood math anymore than I did, but he did a better impression of paying attention while pencil drawing heavy metal demon characters along the text book pages.

I found myself doing four hours of homework each night just for this class. After a few months of it, I had quite enough. All that work was only resulting in a sub par grade, and I felt that time would be better spent being a careless teenager. My friend Milly and I would go cross town to Dianda’s Italian American Pastry in the Mission, where we would spend valuable time eating creme puff-like concoctions. I also had a part time job at an ice cream store, and that was both rewarding and fun until some strange man came in after 9 p.m. to ask if I wanted to spank him. Even this seemed better than attacking math.

My failing math scores never seemed to phase my mother by this time, who already accepted me as the daughter who was bad at school. This was not entirely correct as I always did well in the arts and literature, even though I sarcastically passed off a book report on Erica Jong’s “Fear of Flying” to my teacher in AP English. My flunking math, however, was something she never discussed with her friends. She was always free about disclosing my other failures to her friends, but math was that forbidden subject. She could not tell her people that I lacked that particular gene. In flunking math, her daughter was flunking being Japanese, and that was more than she could handle.

I did, however, decide to attend the last calculus class after a good four month’s absence. My teacher frowned at me, then asked that I save some time to speak with him after class. I had already expected the F, but had not anticipated his final remark. “You should have stayed. You could have gotten a D,” he said.

College had more math plans in my future.

I had to take math in college in order to graduate, so math still was not going to disappear. By this time, my mental approach was far more refined. Instead of appreciating the high sensibilities it took to accomplish math problems, I decided that higher math was entirely useless in my life. No one would ever think to ask me the length of a flag pole or guess the circumference of Tommy Lasorda’s belly. There were calculators and smarter people to determine those things, and I had mad skills at finding those individuals.

I took a Math Without Fear class, a concept idea that tried to eliminate fear of numbers and old teaching methods through the use of tangible visual tools. In dispensing with numbers, the instructor used so many interchangeable items and tried redefining math tools. That just seemed to confuse the process, and math now became an foreign language. In many ways, math without numbers was too discomforting. I preferred to know one singular enemy, and using building blocks, pictures and other aids seemed to only expand my universe of contempt. Of course, I flunked.

Still, I never gave up. I had to take a math class in order to get that one passing grade to graduate with an otherwise stellar GPA. I bypassed the college math requirement of calculus or statistics, opting for the easier challenge of taking the lower requirement of Algebra 2 at the local community college. In no time, years of math failure managed to repeat itself. I spent long hours doing math homework and wasted weekends with well-intentioned friends who tried to tutor me .

I did not, however, flunk this class.. My fellow classmate was someone I had known since childhood, the younger brother of my sister’s friend from judo class. He, and another guy in front of me, managed to slide their final exam papers towards my general direction during the testing period, and I copied their answers.

I passed with a D. Just like the high school teacher predicted I would.

(c) Slow Suburban Death. All rights reserved.

Be First to Comment